Fish Culture Today

Most infected rainbow trout die from whirling disease at a very young age. Those that do survive usually have deformed skeletons and skulls, bulging eyes, and black tails, like the ones pictured above.Photo by Sascha L. Hallett

Most infected rainbow trout die from whirling disease at a very young age. Those that do survive usually have deformed skeletons and skulls, bulging eyes, and black tails, like the ones pictured above.Photo by Sascha L. Hallett

The whirling disease parasite, Myxobolus cerebralis, forms small spores like this one, photographed with an electron microscope. The spores remain viable for dozens of years in the mud, until they are eaten by a small worm known as Tubifex tubifex. When the worms die, they release another phase of the parasite known as a triactinomyxon (TAM) that is ready to infect another fish and complete the life cycle.Photo by Ronald P. Hedrick

The whirling disease parasite, Myxobolus cerebralis, forms small spores like this one, photographed with an electron microscope. The spores remain viable for dozens of years in the mud, until they are eaten by a small worm known as Tubifex tubifex. When the worms die, they release another phase of the parasite known as a triactinomyxon (TAM) that is ready to infect another fish and complete the life cycle.Photo by Ronald P. Hedrick

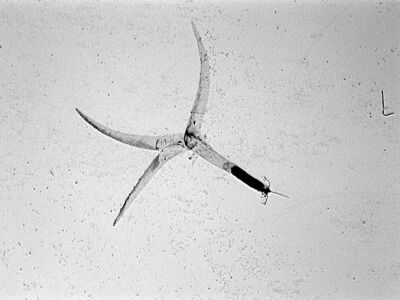

Under a microscope, a Myxobolus cerebralis triactinomyxon looks like a grappling hook. At this stage, the parasite is ready to attach to a fish. When it does, three coiled springs in the tip (the dark portion on the right) shoot into the skin, providing a secure entrance route for the germ capsule.Photo by Vicki Blazer, U.S. Geological Survey

Under a microscope, a Myxobolus cerebralis triactinomyxon looks like a grappling hook. At this stage, the parasite is ready to attach to a fish. When it does, three coiled springs in the tip (the dark portion on the right) shoot into the skin, providing a secure entrance route for the germ capsule.Photo by Vicki Blazer, U.S. Geological Survey

In the decades that followed World War II, reservoirs were built all over the country. Visiting them to fish for rainbow trout became one of America's favorite pasttimes. This picture was taken in 1972.National Archives ARC Identifier 542647 / Local Identifier 412-DA-154

In the decades that followed World War II, reservoirs were built all over the country. Visiting them to fish for rainbow trout became one of America's favorite pasttimes. This picture was taken in 1972.National Archives ARC Identifier 542647 / Local Identifier 412-DA-154

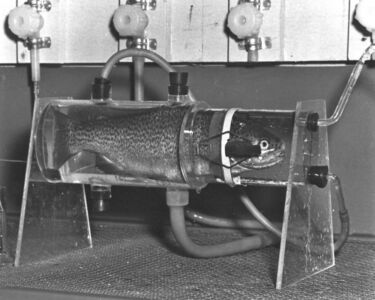

Rainbow trout in nutritional chamber.Photo by Nicholas Mariana. Courtesy of National Conservation Training Center #5297

Rainbow trout in nutritional chamber.Photo by Nicholas Mariana. Courtesy of National Conservation Training Center #5297

Barry Nehring, a Colorado Division of Wildlife biologist, stands in front of the Gunnison Gorge, where whirling disease nearly wiped out a legendary rainbow trout fishery.Photo by Anders Halverson

Barry Nehring, a Colorado Division of Wildlife biologist, stands in front of the Gunnison Gorge, where whirling disease nearly wiped out a legendary rainbow trout fishery.Photo by Anders Halverson

A Colorado Division of Wildlife crew electrofishing in the Gunnison Gorge in September 2006. Some of the crew hold wands that send out a small electric shock, while others wait to net the stunned fish.Photo by Anders Halverson

A Colorado Division of Wildlife crew electrofishing in the Gunnison Gorge in September 2006. Some of the crew hold wands that send out a small electric shock, while others wait to net the stunned fish.Photo by Anders Halverson

A Colorado Division of Wildlife crew electrofishing in the Gunnison Gorge. Some of the crew hold wands that send out a small electric shock, while others wait to net the stunned fish.Photo by Anders Halverson

A Colorado Division of Wildlife crew electrofishing in the Gunnison Gorge. Some of the crew hold wands that send out a small electric shock, while others wait to net the stunned fish.Photo by Anders Halverson

Colorado Division of Wildlife biologists examine a stunned rainbow in the Gunnison Gorge to gather population data and evidence of whirling disease. The department released a strain of rainbows resistant to whirling disease into the river the previous year, this was probably one of them.Photo by Anders Halverson

Colorado Division of Wildlife biologists examine a stunned rainbow in the Gunnison Gorge to gather population data and evidence of whirling disease. The department released a strain of rainbows resistant to whirling disease into the river the previous year, this was probably one of them.Photo by Anders Halverson

A Colorado Division of Wildlife crew electrofishing in the Gunnison Gorge. For bigger fish, a boat like this is used.Photo by Anders Halverson

A Colorado Division of Wildlife crew electrofishing in the Gunnison Gorge. For bigger fish, a boat like this is used.Photo by Anders Halverson

After they hatch, fish are raised in a rearing facility like this one. Here the manager of Colorado's Chalk Cliffs Rearing Unit, Chris Hertrich, examines some young fish, some of which I helped to spawn. They reside in a retrofitted castoff trailer from the Department of Corrections.Photo by Anders Halverson

After they hatch, fish are raised in a rearing facility like this one. Here the manager of Colorado's Chalk Cliffs Rearing Unit, Chris Hertrich, examines some young fish, some of which I helped to spawn. They reside in a retrofitted castoff trailer from the Department of Corrections.Photo by Anders Halverson

Because they need abundant clear water, fish culture facilities tend to be located in beautiful places. This retrofitted trailer is part of Colorado's Chalk Cliffs Rearing Unit, in Nathrop, Colorado.Photo by Anders Halverson

Because they need abundant clear water, fish culture facilities tend to be located in beautiful places. This retrofitted trailer is part of Colorado's Chalk Cliffs Rearing Unit, in Nathrop, Colorado.Photo by Anders Halverson

Here they are, the fish that I helped to spawn, a few months later at the Chalk Cliffs Rearing Unit.Photo by Anders Halverson

Here they are, the fish that I helped to spawn, a few months later at the Chalk Cliffs Rearing Unit.Photo by Anders Halverson

Raceways at Colorado's Crystal River Hatchery.Photo by Anders Halverson

Raceways at Colorado's Crystal River Hatchery.Photo by Anders Halverson

Sometimes you have to ask what this enterprise is all about.Photo by Anders Halverson

Sometimes you have to ask what this enterprise is all about.Photo by Anders Halverson

Anders Halverson tries his hand, spawning rainbow trout at Colorado's Crystal River facility.

Anders Halverson tries his hand, spawning rainbow trout at Colorado's Crystal River facility.

A closeup of Colorado Division of Wildlife's John Riger spawning rainbow trout.Photo by Anders Halverson

A closeup of Colorado Division of Wildlife's John Riger spawning rainbow trout.Photo by Anders Halverson

A closeup of Colorado Division of Wildlife's John Riger spawning rainbow trout.Photo by Anders Halverson

A closeup of Colorado Division of Wildlife's John Riger spawning rainbow trout.Photo by Anders Halverson

Fish culture has changed very little from the 19th century. First squeeze the eggs out of the ripe female by firmly sliding your fingers down the belly, then squeeze the milt out of the male. Swirl it around, and you're done. Provide them a safe place to develop and you'll have some nice fish in a year. This is John Riger at the Colorado Division of Wildlife's Crystal River Hatchery.Photo by Anders Halverson

Fish culture has changed very little from the 19th century. First squeeze the eggs out of the ripe female by firmly sliding your fingers down the belly, then squeeze the milt out of the male. Swirl it around, and you're done. Provide them a safe place to develop and you'll have some nice fish in a year. This is John Riger at the Colorado Division of Wildlife's Crystal River Hatchery.Photo by Anders Halverson

Adam Konrad caught world-record, 43-pound rainbow trout in a Saskatchewan lake. His prize probably escaped from a nearby aquaculture facility and had been manipulated to contain an extra set of chromosomes—a feature that makes such fish grow much faster and larger than normal.Photo courtesy of Otto and Adam Konrad

Adam Konrad caught world-record, 43-pound rainbow trout in a Saskatchewan lake. His prize probably escaped from a nearby aquaculture facility and had been manipulated to contain an extra set of chromosomes—a feature that makes such fish grow much faster and larger than normal.Photo courtesy of Otto and Adam Konrad

A group at the University of Missouri is studying the effects of creatine--the same supplement used by athletes like home-run slugger Mark McGwire--on rainbow trout. Here the fish swims in a Plexiglas tube to measure its endurance. "Sportsmen would likely pay a premium for a fishing experience where the fish struck the bait harder and fought longer," said one of the researchers in a press release.Photo by Steve Morse

A group at the University of Missouri is studying the effects of creatine--the same supplement used by athletes like home-run slugger Mark McGwire--on rainbow trout. Here the fish swims in a Plexiglas tube to measure its endurance. "Sportsmen would likely pay a premium for a fishing experience where the fish struck the bait harder and fought longer," said one of the researchers in a press release.Photo by Steve Morse

Originally native to a narrow band around the Pacific from Baja Mexico to Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula, rainbow trout can now be found all over the world (countries shown in dark gray).

Originally native to a narrow band around the Pacific from Baja Mexico to Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula, rainbow trout can now be found all over the world (countries shown in dark gray).

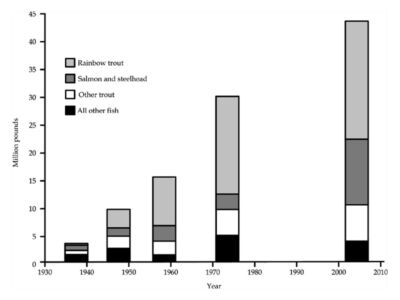

State and federal agencies increased both the number and size of the fish they produced over the course of the twentieth century. By 2004, these agencies were stocking more than 40 million pounds of fish in the freshwaters of the United States every year, close to half of which were rainbow trout.From: Halverson, MA. 2008. Stocking Trends: A Quantitative Review of Governmental Fish Stocking in the United States, 1931-1004. Fisheries 33(2):69-75

State and federal agencies increased both the number and size of the fish they produced over the course of the twentieth century. By 2004, these agencies were stocking more than 40 million pounds of fish in the freshwaters of the United States every year, close to half of which were rainbow trout.From: Halverson, MA. 2008. Stocking Trends: A Quantitative Review of Governmental Fish Stocking in the United States, 1931-1004. Fisheries 33(2):69-75